The Seven Letters

The boarding room at the end of the narrow alley smelled like antiseptic. Mai set a paper cup of rice porridge on the table, took off her mask, and looked at her mother. The woman was thin, lying on her side, left hand clutching the edge of the blanket, right arm limp after a stroke. Since the doctor had said, “If you don’t make the deposit by Monday, we have to give the surgery slot to someone else,” time had started to tick on Mai’s forehead like a countdown.Căn phòng trọ cuối hẻm nhỏ ngập mùi thuốc sát khuẩn. Mai đặt túi cháo trắng xuống bàn, tháo khẩu trang rồi nhìn mẹ. Người đàn bà gầy guộc nằm nghiêng, bàn tay trái nắm chặt mép chăn, tay phải liệt sau cơn tai biến. Từ hôm bác sĩ thông báo: “Nếu không đóng tạm ứng trước thứ Hai, mình phải nhường suất phẫu thuật,” Mai thấy thời gian như đếm ngược trên trán mình.

Mai freelanced as a translator. She used to believe translation could straighten life the way it straightened sentences on a page. But in the past six months, clients had thinned out and her savings were gone. The laptop wheezed, the mouse stuttered, letters jumped in disorder across the screen. Rent, hospital deposit, medication—numbers lined up like a sentence still missing its verb.

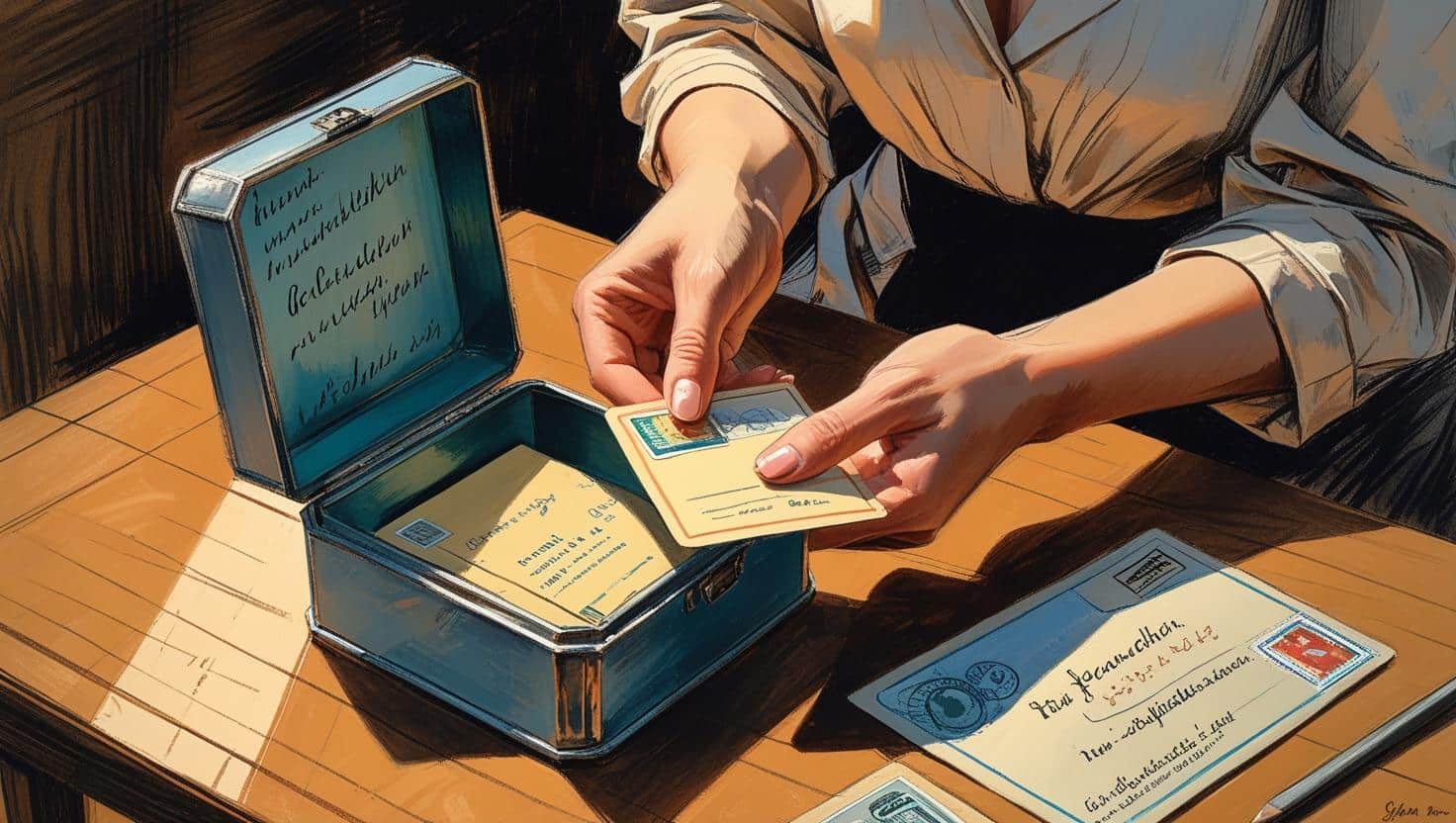

That afternoon, the neighbor, Auntie Le, knocked and handed over a faded silver box. “Someone brought this for you,” she said. “Uncle Lâm from the port—your father’s old friend. He lost touch with you for years. He just found out your mother’s in the hospital.”

Mai froze. Her father had died at sea the year she entered university. The house fell into a silence so loud it rattled. Her mother feared mentioning him. Mai, caught between anger and longing, took the easier choice: she said nothing. Hands careful, she opened the box: a thick envelope, German words slanted across the corner; inside, a handwritten letter, several pages bearing the logo of a foundation, and a thin card like a library pass. None of it was Vietnamese. Not even English—her working language.

Her mother blinked and tried to lift her left hand. Her lips shaped the air: “Translate… please.”

Mai spread the letter out. The handwriting was neat, the dots unfamiliar. She opened a free German–Vietnamese dictionary app. It spat out clumsy sentences where every word seemed yanked to the wrong place. She sighed. Even outside her specialization, she knew one thing: to translate is to listen for how the writer breathes.

She read again and again, recognizing certain anchors: für dich—for you; Frist—deadline; Stiftung—foundation; something with Sprach—language. On the second page, a line in italics: „Sieben Buchstaben.“ Seven letters.

Seven letters of what? She wrote it in her notebook. Coffee. Chair closer to the table. Yellow lamp on. Evening leaked over the window; motorbikes hissed home in the alley. Her mother slept, breath rough but regular.

She began like a child on a first bicycle—tipping over and righting herself—picking through words and laying them into context. “To my daughter,” the letter began. Mai paused. “I chose bridge welding because I like standing between two banks, watching people find their way to each other.” He wrote of his years in Europe, strange food, a cold that bit bone, and the ache of home when the night went long. “I’m not good with pretty words, so I borrow letters to help me speak.”

Midway through, the tone tightened like a contract. Her father described a program he’d joined years earlier with a foundation in Berlin—one that kept a pre-paid scholarship for students of… translation. He had made an advance “escrow donation” so that his daughter—“even if she didn’t choose or didn’t yet dare to choose the trade of words”—would have a seat to claim, “another bridge to cross life.” But to receive it, the beneficiary had to submit a translation of this very letter, along with a seven-letter code hidden inside. Deadline: the end of this month.

Sweat beaded at Mai’s hairline. Today was Friday.

The appendix bore the foundation’s logo. A long block of German, then English—Mai exhaled. The English explained that alongside the scholarship, the foundation ran an emergency medical guarantee for the recipient’s immediate family; they could send a guarantee letter to the hospital within 24 hours if the documents and… the seven-letter code were provided.

The room brightened. But how would she—within two days—translate the entire letter from German and find the code? If she mistranslated or missed the code, she could lose everything. She rolled up her sleeves and remembered a teacher’s line: “Meaning hides in the seams of a sentence.”

Clues. The first letter of each paragraph? The first sentence of each section? An acrostic? She copied the initial letters of the seven main paragraphs. G L O C A L … She huffed a laugh. Glo… what? She wrote the next, then the next. At last: G L O C A L E. A strange word that sounded like glocal—global and local. Seven letters. GLOCALE. GLOCALE.

She refused to celebrate early. She checked again: seven main paragraphs, seven initials, and in the last paragraph her father had written, “You’ll understand why I chose these seven letters when you finish the translation.”

Mai translated in an unbroken seam until dawn. At times she itched to pick a “prettier” word, then stopped herself: this was her father’s voice—plain and a little clumsy. She kept the clumsiness. When she eased the last sentence into Vietnamese, her eyes stung: “If you’ve reached this line, you’ve done two things: one, translated my letter; two, forgiven me a little.”

Saturday morning, Mai emailed the foundation her translation, scans of ID and hospital documents. In clear English, she explained the urgency and, on the last line, bolded the code: GLOCALE. She pressed send.

All day, she pushed her mother’s wheelchair to tests and pre-op checks. Her phone vibrated with spam, not with the only reply that mattered. Evening. A new email. Her heart lurched.

“We confirm receipt of your translation. The code matches. Please allow 12–24 hours for file review.” Mai slid down the corridor wall, crying from fatigue and fear. Monday was the hospital deadline. If the letter didn’t arrive in time, the slot would close like a door in her face.

That night she slept on a folding chair by her mother’s bed. Cold air blew through the gap in the curtain. Her mother opened her eyes and whispered, “Did he… write anything for me?”

Mai clasped her hand. “He did,” she said. “He wrote: if you translate to the last letter, you’ll know why seven letters can make a bridge.”

Her mother closed her eyes, lips softening. “He was clumsy. But he loved us.”

Sunday, 8 a.m.—an email flashed: “Emergency Guarantee Letter – Approved.” Mai’s fingers shook. Inside: a hospital guarantee in English and Vietnamese, digitally signed, with a contact number. The final paragraph punched the breath from her chest: “We also confirm a Translation Scholarship for Nguyễn Mai, valid for two years, with an option to defer one year for caregiving.”

She ran to the finance office. The clerk read the email and called to verify. A beat later, the clerk looked up with a smile. “We’ve received the original. Sign here. Monday’s surgery slot is held.”

Mai leaned against the wall as if someone had just laid a bridge from despair to relief. She returned to the ward and held her mother. “It’s done.”

That afternoon, she finally translated the last appendix page she’d skipped in exhaustion—the explanation of GLOCALE: “All my life I welded bridges—big ones. But our family lives in a small alley. ‘Glocal’ is the small tied to the great. You translate a letter in our tiny room, and it reaches a hospital, then a city far away. Those seven letters are your bridge.”

On the margin, a few wobbly lines in Vietnamese, punctuation wrong, handwriting almost childlike: “Mai, translate this sentence into German for Dad when you have time. Thank you, my translator.” Mai laughed and cried at once. He had been relearning Vietnamese to write a few last lines in the language of home. He wasn’t fluent. He tried. That was poem enough.

Monday, her mother entered surgery. Mai stood by the window, watching the hospital trees move, one hand on the plastic sleeve holding both originals and her translation—plain, tidy, unshowy. She thought of nights spent typing phrases like “functional equivalence” and “fidelity to source,” of deadlines missed because a cousin had a fever, of half-finished documents waiting for clients to answer. Translation, she realized, wasn’t a “fancy typing service,” as someone once joked. It was the work of bringing banks closer.

The operation ended near noon. The surgeon stepped out, mask off, eyes shadowed but kind. “She’s stable,” he said. Mai bowed, hands shaking the way they do when you finally solve a sentence that wouldn’t yield. By afternoon, her mother woke. The hand that had refused to move twitched. She squeezed Mai’s fingers. “Thank you,” she whispered, “my translator.”

In days that followed, the foundation emailed about scholarship procedures. If travel was difficult, they said, she could begin online and receive a modest stipend. A staff member asked—half teasing, half sincere—“Who translated the letter? It’s clear and keeps the writer’s voice.” Mai answered, “The writer’s daughter.”

A month later, Mai framed the bilingual letter and hung it on the flaking wall of their room. The frame was cheap, the glass scuffed, but the space felt different. Her mother could sit up now and practice curling and uncurling her fingers. When she tired, she looked at the frame and smiled. “You hung it in the perfect spot.”

Mai opened her laptop and dropped into a new translation—a medical guide for a family with a child who had a rare disease. The young mother called from Hà Giang, voice shaking: “I don’t understand these English terms.” Mai said gently, “Send them to me. I won’t charge. This is something you need to understand.” She remembered the helplessness of reading words that didn’t belong to you. She wanted to be a bridge someone could hold.

Late that night, she drafted an email asking to defer one semester. She didn’t want to go far yet; her mother still needed her. But she had already left, in a way—crossed into a world where words weren’t walls but doors.

Before lights out, she stood in front of the frame for a long time. On yellowed paper, GLOCALE glimmered. She suddenly understood everything: a bridge welder who built not just concrete spans for strangers, but a seven-letter crossing that linked a small family to a foundation across the world; a young translator, stuck and scared, to a future that finally spoke her name.

She touched the glass and said, as if into the ear of a stubborn paragraph, “I’ve finished translating, Dad.” Then she smiled, turned back to the desk, and opened a fresh file named “Bridges Made of Words.”

Outside, the alley was noisy, motorbikes slicing through puddles left by the rain. Somewhere, a span had just locked into place. Not steel, but speech. Translation, she knew now, was the key that turns in a lock everyone assumes is rusted shut—the lock on hope, on hands finding each other, on the “thank you” that bursts out through a throat made for sobbing.

And in that little room, as her mother breathed easier, as keystrokes replaced labored gasps, as one letter crossed a language to save a surgery, another life began to shift—dark to light, helpless to in-motion, from a tired daughter to a true translator: the person who gets this shore to that one.